As I find myself at the end of the year thinking back on what I read in 2022, sadly only a few books spring immediately to mind. For some time now I have felt a growing distance between me—the reader—and the book in hand. I am still not sure why. I’ve been reading fewer books per year, which might suggest that I am reading slower and absorbing more. However, that has not proven to be the case. When comparing this reading year to last year, I see a similar pattern: a smattering of new discoveries bolstered by the works of long-time favorite writers. Reading these latter writers is always a bittersweet experience, as many of them are dead and I have either read all or most of their works by now. So it is with a somewhat heavy heart that I find myself reading the final few titles of writers such as Thomas Bernhard, of whom this year I closed out my reading of all his available prose translated into English. Although rereading books is a practice I rarely engage in, I find myself more drawn to the idea as I reflect on whether it would be more rewarding to rediscover and/or find new layers of appreciation in books I’ve already read than to continue casting about for new gems that I never seem able to unearth. It may soon be that I stop seeking the new altogether and retreat to my reading cave with a stack of favorites. But for now, here are my top reads for this year, in chronological order, with a few notes and links to my reviews. All books were either rated 4 or 5 stars on Goodreads and tagged with my ‘somewhere else’ tag, which denotes a book that has truly taken me somewhere else.

Swallowing Mercury by Wioletta Greg: I have a special fondness for Polish literature—I wouldn’t say I’ve read a lot of Polish writers, but all the ones I have read stand out in my mind, head and shoulders above many other writers. Unfortunately, Greg’s linked follow-up to this semi-autobiographical coming-of-age novel did not measure up to the poetic magic found in these pages.

The Orchid Stories by Kenward Elmslie: One of the strangest books I’ve ever read. I can’t say the experience was consistently enjoyable, per se, but it certainly was worthwhile.

The Death of Conrad Unger by Gary J. Shipley: As you can see, I didn’t actually write anything about this book, only pulled a few quotes that struck me. Discovering Shipley’s writing was a reading highlight this year, though as with the fiction of writers such as Maurice Blanchot, I sometimes find it hard to write about it. But Shipley’s unique style of philosophical horror fiction is an important strand of literature needling its way forward into the future of our doomed planet.

Terminal Park by Gary J. Shipley: Relevant reading for dark times.

Failure to Thrive by Meghan Lamb: Meghan Lamb continues to impress me and remains one of the most interesting younger American writers I’ve come across. So much of the contemporary American literary fiction landscape is dominated by craft-oriented writers whose fiction leaves me cold. Lamb is one of the few I’ve discovered who is clearly dedicated to her craft yet still writes compelling stories with real emotion woven into them.

Frances Johnson by Stacey Levine: I’d read Levine’s novel Dra– a few years ago and really enjoyed it but hadn’t gotten to any of her other books until this year. I liked this darkly whimsical tale of a woman approaching middle age so much that I also read Levine’s two story collections this year.

The Lighted Burrow by Max Blecher: Blecher’s novel Adventures in Immediate Irreality is a favorite of mine, and so I was thrilled to see that Sublunary Editions was publishing this one in English translation by the talented writer-translator Christina Tudor-Sideri. While not as irreal as Adventures, this is still a powerful book of autofiction drawn from Blecher’s time in sanatoriums across Europe.

Scarred Hearts by Max Blecher: Craving more Blecher after consuming The Lighted Burrow, I turned to his only other work of fiction, which offers a much more straightforward story than his other books. Still centered on illness and convalescence, this one is a little more distanced in the telling, in part due to the third-person viewpoint. All of Blecher’s work is essential in my view, though. I’ve only sampled his poetry but expect to delve into it at a deeper level soon.

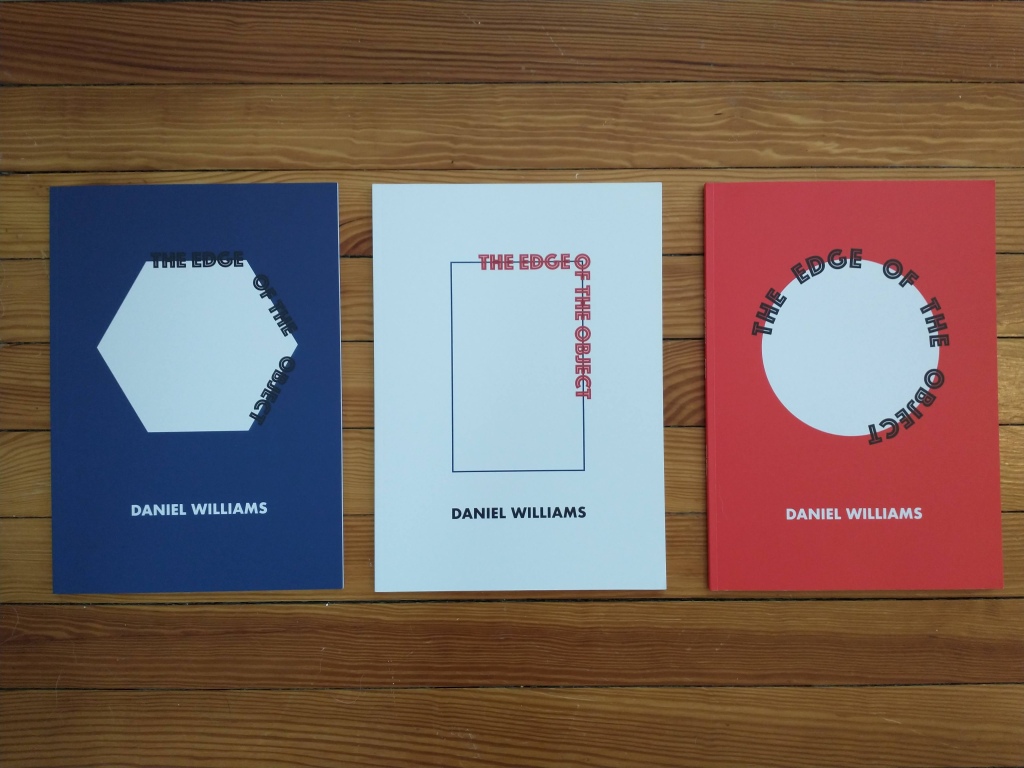

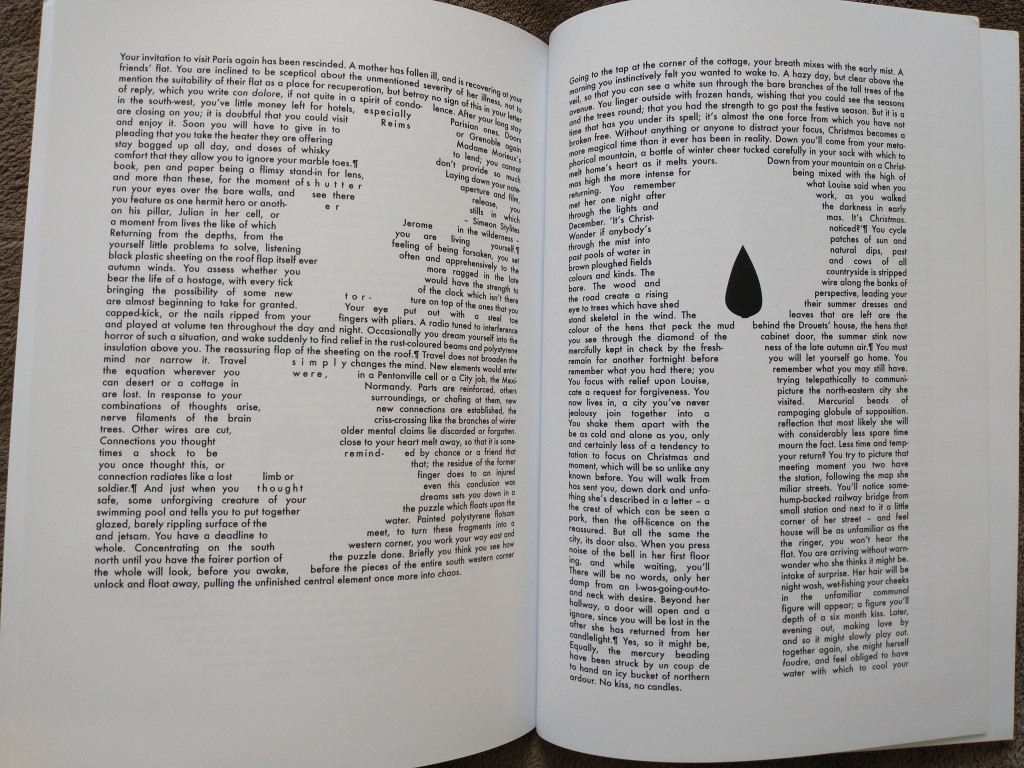

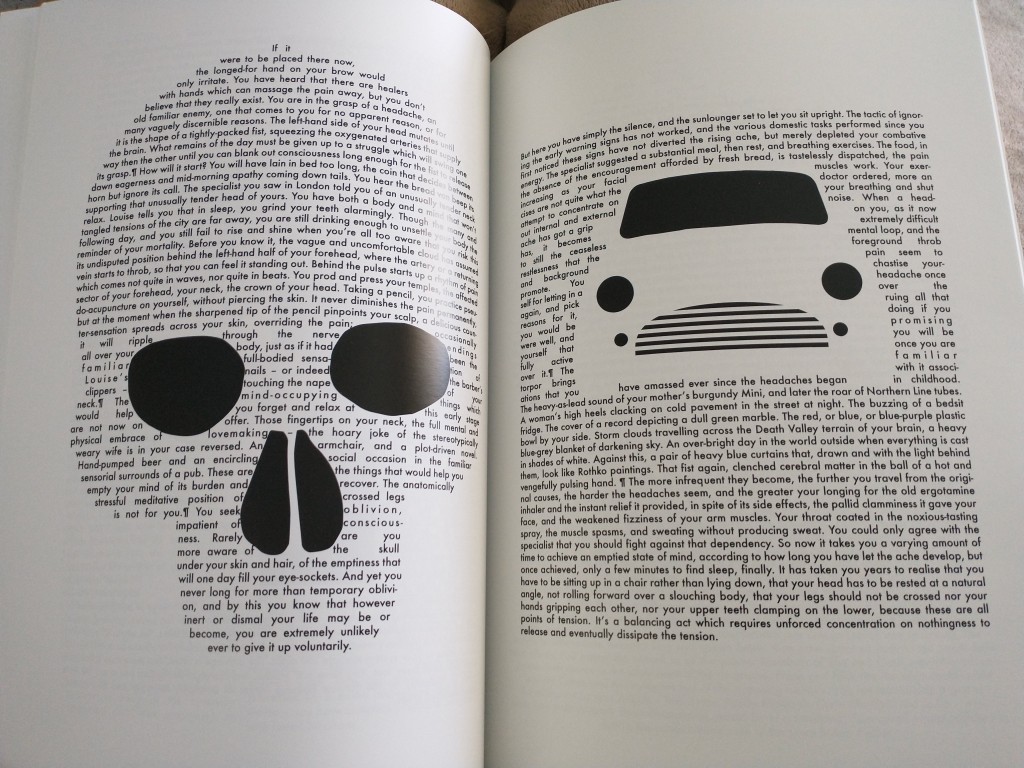

The Edge of the Object by Daniel Williams: I’ve been reading and enjoying Daniel Williams’s writing (mostly) online for a long time so was happy to find that his debut novel was being published. The craftsmanship that went into the production of this book is as much on display as Williams’s deftness with the English language. Truly a one-of-a-kind book.

Beyond the Curve by Kōbō Abe: This is a ‘best of’ type collection of Abe’s short fiction and while not every story is a knockout, many of them are very good. I find Abe to be consistently interesting and his recurring themes of alienation, isolation, social ineptitude, anxiety, and paranoia always resonate with me.

New and Selected Stories by Cristina Rivera Garza: I read this one in a group discussion forum on Goodreads. Rivera Garza is always thought-provoking, though overall I think I prefer her novels to her short stories. The stories that held the most appeal for me in this collection were those that shared common thematic and stylistic ground with her two excellent novels The Iliac Crest and The Taiga Syndrome.

The Dark Bough by Henri Bosco: Bosco’s masterpiece Malicroix was a favorite of mine from 2020, and ever since then I’d been wringing my hands over whether to spring for a copy of this other novel of his. Malicroix had been a NYRB reissue, but this one was very old and out of print. Probably by most actual book collectors’ standards the prices for this online were not much to fret over, but I don’t buy a lot of books in general (diehard library user here), and rarely do I spend over US$20 for a book. However, after exhausting all efforts to find this through interlibrary loan I finally gave in and sprang for a used copy. Though the novel is not at the same level as Malicroix, it was still well worth the money spent. I hope that NYRB or another publisher decides to reissue this one, too.

Thomas Bernhard: 3 Days: Three days of Thomas Bernhard sitting on a park bench and talking about himself and other matters—what’s not to love? Pair this with Bernhard’s memoir Gathering Evidence and you will receive as comprehensive an image of Bernhard the person as he was willing to make public.

Prose by Thomas Bernhard: Bernhard is much more well-known for his novels than for his short stories, so I was a little wary approaching this one, but it ended up being very good and in a slightly different way than his novels, which was a pleasant surprise.

The Anniversary of Never by Joel Lane: Lane is a favorite ‘weird fiction’ writer of mine and this collection of his was recently reissued. His fictive milieu is not to be rivaled in its unique flavor: a dark gloomy West Midlands landscape peopled by lost souls struggling to connect.

Watchmen by Alan Moore: Yeah, I finally read it and it was good. Pretty much rendered any subsequent superhero comics irrelevant.

Three Novellas by Thomas Bernhard: Clearly I became gluttonous in my reading of Bernhard again, but it was worth it—his writing was a tangible flotation device to cling to when I felt like I was sinking.

Under the Sign of the Labyrinth by Christina Tudor-Sideri: This was the first of Tudor-Sideri’s two books that I read this year. She is a challenging writer to read—restless and relentlessly questioning in her prose, often retreating to ambiguity—but always rewarding.

Disembodied by Christina Tudor-Sideri: Tudor-Sideri’s first novel is a single paragraph of digressive and fragmented prose, delivered by a narrator in her final breath.

Chasm by Dorothea Tanning: The only novel by Surrealist artist and writer Dorothea Tanning. A rare single-day read for me that checked a lot of my personal reading boxes.

The Voice Imitator by Thomas Bernhard: I’d been avoiding this book for years because I couldn’t imagine Bernhard’s writing in such microscopic form, but I ended up really enjoying these early little fictions of his.

Private Property by Mary Ruefle: It had been quite a while since I’d read Mary Ruefle, but she’s always been a favorite of mine so I knew I’d get back to her sooner or later. This one is up there close to her best work in the form where I think she excels the most—short prose pieces that range from the poetic to the essayistic.

On the Mountain: Rescue Attempt, Nonsense by Thomas Bernhard: This was Bernhard’s earliest known prose work and the one he chose to have published last in his lifetime. It’s possible that only the most dedicated Bernhard readers would enjoy this, for it is very much an embryonic work for such a storied writer, but I found it to be fascinating and a fitting close to my reading of his prose works. (What now? Perhaps I will begin staging his plays as solo shows in my house…)

Play It as It Lays by Joan Didion: Finally got around to reading some Didion and it didn’t disappoint. This falls in line with other novels I’ve read from the same era by women writers such as Ann Quin, Renata Adler, and, to a lesser extent, Joy Williams. But Didion’s style is distilled to such a purity of focus that it perhaps encapsulates that particular zeitgeist of the late 1960s/early 1970s best of all.

The Shutter of Snow by Emily Holmes Coleman: This novel based on Coleman’s own experience in a psychiatric hospital delivers a pitch-perfect blend of horror, outrage, pathos, and absurdity. To be filed alongside Ann Quin’s The Unmapped Country, Anna Kavan’s Asylum Piece, and Leonora Carrington’s Down Below as another exemplar of literature exposing the cruelty, hypocrisy, and inhumanity inherent in the forced institutionalization of women, in particular.